Museum History

The Field Museum connects all of us to the natural world and the human story.

A Little History

Located on Chicago’s iconic Lake Michigan shore, the Field Museum opened its current building to the public in 1921—but our story began years earlier.

Our collection grew out of items on display in the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in the “White City.” The exposition delighted visitors with 65,000 exhibits filled with natural wonders and cultural artifacts, many of which later found a permanent home in Chicago at the newly created Field Columbian Museum. Our museum name still honors Marshall Field, who donated $1 million to make the collective dream of a permanent museum a reality.

Since opening the Museum in 1894, our collection has grown to nearly 40 million artifacts and specimens. The breadth of our mission has expanded, too. We continue to research the objects in our collections, as well as document previously unknown species, conserve ecosystems in our backyard and across the globe, educate budding scientists, invite cross-cultural conversation, and more—all to ensure that our planet thrives for generations to come.

We're In This Together

It takes hundreds of people working behind the scenes and with our visitors to operate a world-class museum.

From the designers who plan and build our exhibitions, to collections managers who prepare, catalog, and care for our specimens and artifacts…

From the staff who take care of the building, to educators ready to answer questions and help visitors explore the natural world up close…

From co-curators who work with Indigenous peoples to create inclusive exhibitions, to community organizers who build bridges with groups in our backyard and around the world…

From communicators who share our stories with the world, to tour guides and volunteers who make the Museum friendly and accessible…

We all work together to welcome visitors through our doors and pursue our mission. Working toward a better world is a big job. Meet Our Staff

Our Huge Collection is Just a Fraction of What we Do

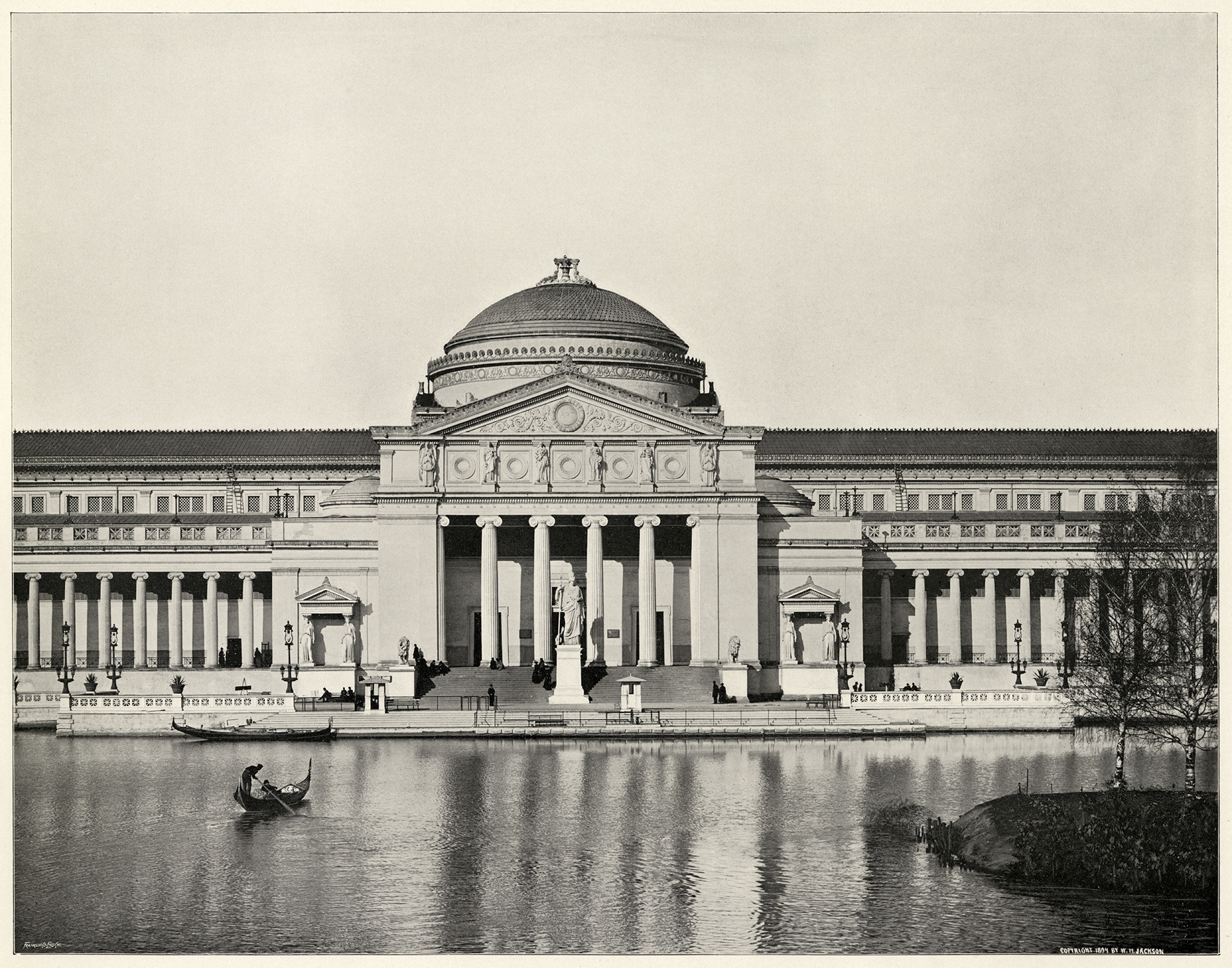

World's Columbian Exposition

In 1893, Chicago hosted the World’s Columbian Exposition, organized to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s arrival in “the New World.” The six-month event drew 27 million people to the city.

A glittering showcase of art, architecture, technology, and global culture, the event introduced the world to the Ferris wheel, newly invented products like Cream of Wheat, and rare items from around the world. Tens of thousands of these items would go on to form the original collections of a brand-new natural history museum in Chicago.

Establishment

Frederic Ward Putnam, Head of the Department of Ethnology at the Columbian Exposition, envisioned a museum that would grow out of the Exposition before it even began. He is often considered the founder of the Field Museum, as he advocated for its establishment among Chicago’s cultural, intellectual, and capitalist elites.

“To this great city is now offered an exceptional opportunity of establishing a grand museum of natural history, as a permanent result of the World’s Columbian Exposition. Surely this opportunity must not be lost. Arrangements should be made without delay to thus add the culture of the natural sciences to the present attractions and importance to the city…” (Boyer, 1993)

Putnam found an ally in Chicago businessman Edward E. Ayer, who would later become the Museum’s first president. Ayer called upon Marshall Field, a local business magnate known to support any plan for increasing Chicago’s access to culture and education, to solicit his support. After some consideration, Field offered $1 million—equivalent to nearly 36 million in today’s dollars. Field’s instrumental contribution—along with the contributions of other wealthy donors—ensured the establishment and permanence of a great museum in Chicago.

The state of Illinois approved the charter that officially created the Columbian Museum of Chicago—which was quickly renamed the Field Columbian Museum to honor its first major benefactor. On June 2, 1894, the museum opened to the public in the Palace of Fine Arts Building in Jackson Park.

Early acquisitions, collections, and leadership

The collections began with items that had been on display at the World’s Columbian Exposition. Many of the Museum’s early scientific staff were central to their collection and curation.

The first chair of the Geology Department, Oliver C. Farrington, came to the Museum at the time of its founding in 1893. Among the first items in the geology collections were gems from the Tiffany & Co. display from the Columbian Exposition, which was acquired by the Museum in its entirety.

Frederic Ward Putnam gathered extensive archaeological material from the Americas for the Columbian Exposition, including pre-Columbian gold ornaments and a large collection of Native American material cultureobjects—which became the foundation of the Museum’s Anthropology Collection, and Putnam its first curator.

Additional anthropological items and geological specimens, including fossils, a mastodon skeleton, and model of a woolly mammoth were acquired from the expansive Ward’s Natural Science Establishment exhibit.

The first specimens in the Museum’s botany collection were plant materials of economic use that had been displayed in the Horticulture Building at the Exposition. Many of these items were solicited by Charles F. Millspaugh, who became Curator of Botany.

Curator C. B. Cory donated his collection of 19,000 bird specimens to the museum in exchange for departmental status for Ornithology. In this early period, Curator David Giraud Elliot, an eminent mammalogist and ornithologist, led Zoology (except Ornithology) with Assistant Curators O. P. Hay and later S. E. Meek.

The Palace of Fine ARts building in Jackson Park, originallythe fine art gallery for the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition, was the Field Museum's first home.

In 1894, collections on display in the West Court included a wedge of a giant redwood tree, a mastodon skeleton, and a mammoth model.

Early expeditions

Within days of the Museum’s founding, botanists and zoologists set out on expeditions: conducting inventories of global tropical diversity, charting regions previously unexplored by Western scientists, building Museum collections, and compiling data that would inform future conservation work.

Charles Millspaugh set off to collect plants in Mexico’s Yucatán region.

In 1896, Chief Taxidermist Carl Akeley and Zoology curator David Giraud Elliot organized the first expedition to Somalia by a North American museum. The crew brought back the first of our extensive African bird and mammal holdings. In his writings from the expedition, Elliot sounded the alarm about rapidly vanishing wildlife and emphasized the importance of the Museum’s role in documenting it.

The library is founded

In 1894, the Field Museum Library was founded to serve the research and education needs of Museum staff, students, volunteers, and visitors. Its formation began with the transfer of books from the department libraries of the World’s Columbian Exposition, and the collection expanded rapidly through partnerships, donations, and the efforts of Museum staff and librarians.

Elmer Riggs

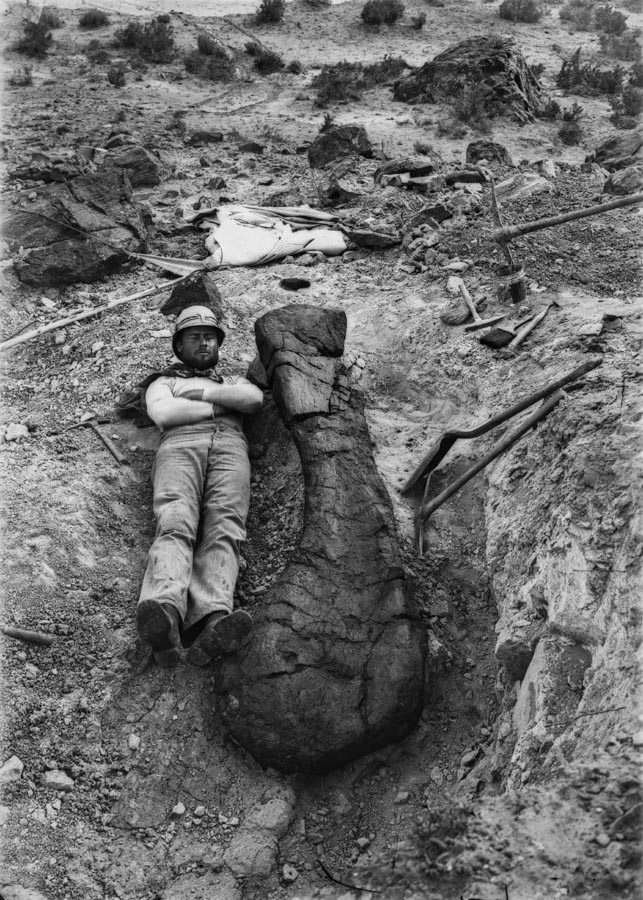

In 1898 the new Department of Geology hired its first paleontologist, Elmer Riggs, whose research focused on fossil mammals. Riggs spent several years collecting and studying dinosaurs to give the Museum’s displays a jump-start, then pivoted to spend the remainder of his career working on fossil mammals.

Riggs collected dinosaurs from the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods in Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, and Alberta, Canada. He led many expeditions to the western United States in search of fossil mammals.

On an expedition to a site near Grand Junction, CO, Riggs and his team discovered the holotype of Brachiosaurus, which Riggs named and described. Riggs’s legacy also includes an impressive collection of Cenozoic mammals he brought to the Museum from Bolivia and Argentina.

Preparator H. William Menke, a member of the first three Field Museum paleontology expeditions led by Elmer Riggs, the museum’s first paleontologist, photographed next to the humerus of the holotype of Brachiosaurus altithorax.

Carl Akeley

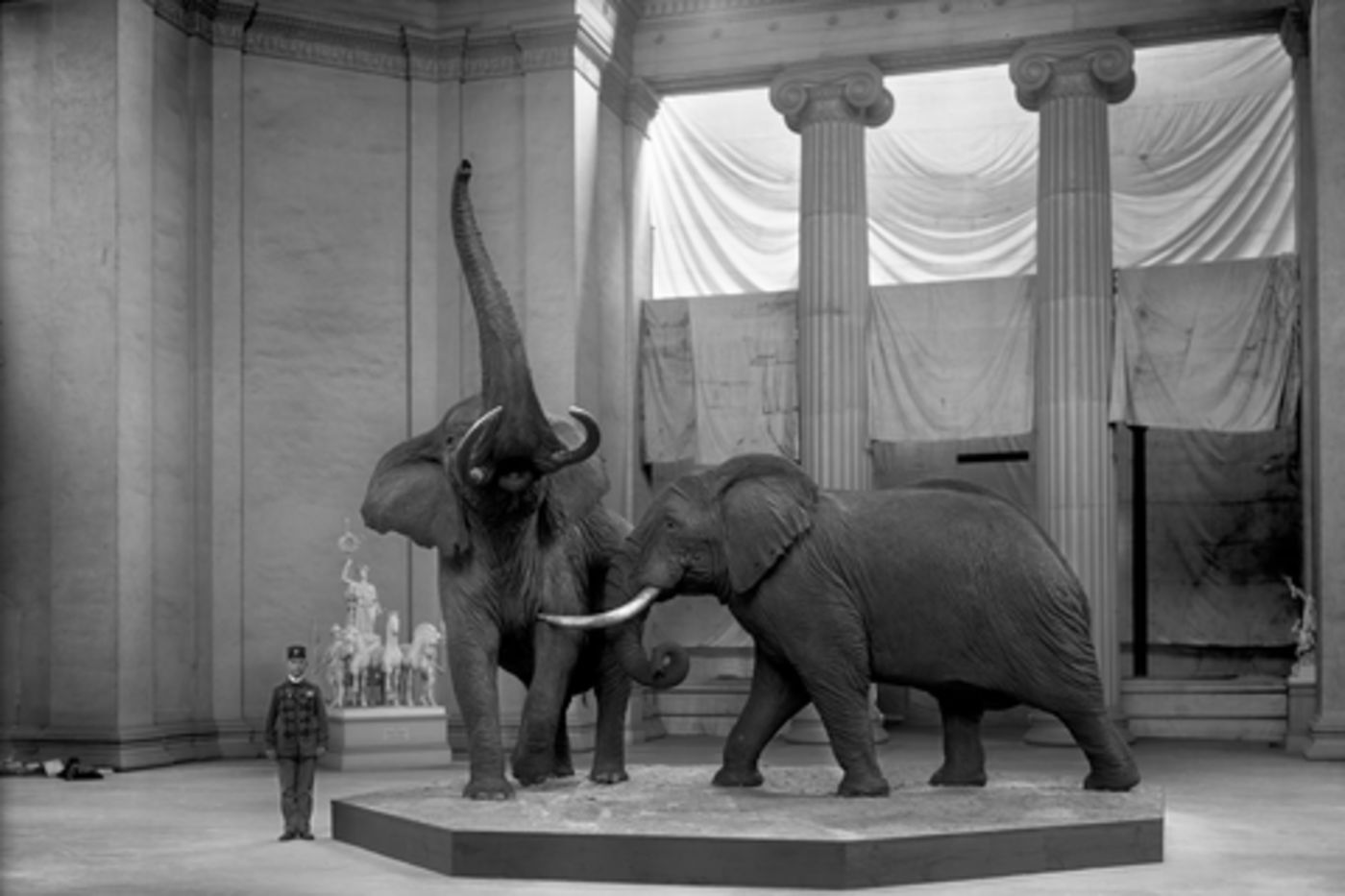

Taxidermist Carl Akeley was hired into the Department of Zoology in 1895. Akeley was a naturalist, sculptor, writer, and inventor. During his fourteen years with the Museum, he perfected his sculptural methods in taxidermy and created vivid depictions of animals in their natural habitats.

Akeley’s 1902 series of dioramas depicting the white-tailed deer in spring, summer, fall, and winter, known as the Four Seasons, set the standard for taxidermy and museum habitat groups for decades to come. His mounts of two fighting African elephants still tower over visitors in Stanley Field Hall.

The expansive and meticulously created collection of taxidermied specimens at the Field Museum would not be what it is without Akeley’s contributions. Akeley's pioneering techniques, forward thinking, and adventurous nature have inspired many scientists and artists alike, and his legacy lives on in the many dioramas still in our halls today.

Carl Akeley’s fighting African elephants, shown here in their first location at the Field Columbian Museum in Jackson Park, remain on exhibit today, in the Museum’s Stanley Field Hall.

Diorama of Virginia deer in their natural habitat in summer from Carl Akeley’s Four Seasons, on display at the Field Museum since 1902

Stanley Field

Stanley Field, nephew of founding museum benefactor Marshall Field, became president of the Field Museum in 1908, a role he held for 56 years. Field was instrumental in relocating the Museum to its present location. The iconic Stanley Field Hall is named in his honor.

A new home

The museum’s extensive collection continued to grow, but the Palace of Fine Arts building was not aging gracefully. The search began for a site to rebuild the museum.

After much deliberation on the site and style of the museum’s new home, construction began in 1915 on a new building at a site near Grant Park. The building, designed by architect Peirce Anderson of Graham, Anderson, Probst and White, cost $7 million to build and was part of Daniel Burnham’s 1909 Plan of Chicago.

In March 1920, crews began moving objects from the museum’s original location to its new home.

On May 2, 1921, crowds lined up for miles to visit the Field Columbian Museum on opening day.

Cornerstone ceremonies with Trustees, executive officers, administrators, and curators

Chicago Architectural Photo Company (c) The Field Museum, GN90799d FMBL276w

An empty Stanley Field Hall photographed in 1920, the year before the museum reopened at its location south of Grant Park.

Courtesy of: C. H. Carpenter. (c) Field Museum of Natural History.

During the move from Jackson Park, displays were loaded into crates and transported by rail and horse-drawn carriage, like this case full of birds, which includes a Mute Swan and Scarlet Ibis.

On opening day, crowds lined up for miles to visit the Field Columbian Museum in its new home near Grant Park.

Expeditions continue, collections grow

Expeditions continued on through World War I.

The Museum’s anthropology research expanded worldwide, with expeditions to South and Central America in the 1920s and ‘30s.

The 1920s brought the heyday of zoological collecting, with expeditions to Africa, South America, and the Pacific.

Research continued through the Great Depression through the postwar period, led by a who’s who of American zoologists: herpetologist Karl P. Schmidt, ornithologists Emmet Blake and Austin Rand, mammalogist Dwight Davis, and primate expert Philip Hershkovitz—all of whom were Field Museum curators.

New neighbors

Shedd Aquarium and Adler Planetarium opened in 1930, joining the Field on Chicago’s lakefront south of Grant Park. In 1998, the “Museum Campus” was officially completed after crews removed the roadways that bisected the campus and created walkable areas of green space that visitors enjoy now.

Aerial view of the Museum Campus, including the Field Museum, Shedd Aquarium, and Adler Planetarium, circa 1998

Bolstered by the Works Progress Administration

Beginning in 1933, the Field Museum hired workers from the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a New Deal agency created to employ people on public-works projects during the Great Depression. Each year, The Field Museum employed approximately 200 WPA employees, which augmented the 189 Museum employees at the time. A few were hired on a permanent basis after the WPA program ended in 1943.

WPA workers at The Field Museum had varied assignments that were paid for through the agency. Some carried out scientific research projects, while others assisted in tasks requiring artistic ability, such as creating murals, dioramas, and plant models. Many provided clerical work and skilled labor: overall, the Museum's Division of Printing was one of the largest employers of WPA workers. All of the scientific divisions benefited by the large numbers of relief employees assigned to tasks like cataloging, typing manuscript records, filing, cleaning of specimens, and mounting photographs.

K.P. Schmidt

Karl Patterson (K.P.) Schmidt was a world-renowned herpetologist and curator with The Field Museum from 1922 until 1957. He began his career at the American Museum of Natural History before coming the the Field where he took a post as Assistant Curator of Reptiles and Amphibians, eventually becoming chief curator of Zoology in 1941. Among his numerous honors, Schmidt was awarded the Guggenheim Fellowship in 1932, and elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1956. Over the course of his career, Schmidt named more than 200 species of reptiles and amphibians; Many scientists named species and subspecies of reptiles and amphibians for Schmidt.

On September 25, 1957, the director of the Lincoln Park Zoo sent a snake to The Field Museum for identification. Schmidt concluded that based on the snake's behavior, it was a boomslang, native to Sub Saharan Africa. After taking the snake from a colleague without precautions to prevent a bite, Schmidt was bitten on the thumb. The venom of the boomslang is a hemotoxin, which means that it disrupts blood coagulation in humans; essentially, as the venom spreads it causes fibrinogen in the bloodstream to form clots. The fibrinogen is then not available to stop bleeding. This leads to bleeding in major internal organs and possibly death. Schmidt did not seek medical attention, but kept a journal of the symptoms he experienced, recording all of the effects of the bite in graphic detail. Within 24 hours, Schmidt was pronounced dead. A transcript of his journal was published by the Chicago Tribune in an article titled "Diary of Snakebite Death!" on October 3rd, 1957.

Carl Cotton

The Field Museum’s tradition of excellence in taxidermy and exhibit preparation was continued by Carl Cotton, the Museum’s first Black taxidermist—and possibly the first professional Black taxidermist in Chicago.

Cotton taught himself taxidermy at a young age, starting by artistically mounting small animals he found dead in his Chicago neighborhood. In 1940, at age 22, Cotton wrote to the Director of the Museum in search of a taxidermy job but was turned down. He wrote again years later in 1947, requesting a position as a volunteer. Cotton was hired the next week—and his prowess and skill were so evident that just one month later Cotton was hired on to a full-time position in the Division of Anatomy.

Among his achievements are the Alligator Snapping Turtle, created using the Walters method. Developed by Cottton’s mentor Leon Waters, Cotton perfected the process and trained other taxidermists to use it.

One of his most stunning pieces was Colorful Birds, created with Staff Artist E. John Pfiffner. Colorful Birds features 56 brilliantly colored birds perched on twisting and turning metal curves reaching 16 feet in the air. While the display was dismantled in 1990, its birds can still be seen throughout the Ronald and Christina Gidwitz Hall of Birds, identifiable by their perch on the original sculpture’s metal form.

In addition to birds and reptiles, Cotton skillfully taxidermied fish, mammals, and insects. Cotton was a unique talent who influenced nearly every department at the Field Museum and beyond.

The environmental movement is born

Although active conservation efforts were some years off, the Field’s interest in environmental issues remained constant in our scientific endeavors. The environmental movement of the 1960s and ’70s increased the visibility and urgency of conservation, and the Field expanded its role in both local and international conservation efforts.

Innovations in collections data

In the late 1970s, Field Museum began digitizing collection data. The Field Museum was an early adopter of new computer technology.

Taking action

A turning point came during our centennial celebration in 1994. It started with a small group of researchers, spearheaded by Debra Moskovits, who has served on the Museum’s staff since 1985. The team’s mission: translate the Field Museum’s rigorous science into direct action for conservation and cultural understanding.

The team traveled to South America to perform the Museum’s first of many rapid biological inventories, expeditions designed to document natural areas and the species that live there, and make recommendations for conservation efforts. These efforts so far have led to the protection of 33 million acres of forests and waters—and the formation of the Keller Science Action Center.

Reckoning with our colonial past

The Field Museum’s anthropology collections represent cultures from around the globe, from the earliest human societies to thriving modern communities. The millions of items in our collections hold countless stories about how they were made, used, found and collected, by whom, and for what purpose. While many of these histories reflect a deep respect and care for the communities involved, others—especially those from the late 19th and early 20th centuries—are highly problematic.

Many collectors of that era believed that the scientific benefits of acquiring certain cultural items and human remains outweighed any harm inflicted on the communities from which they originated. Some collectors were indifferent to the damage they caused to these communities, who were already under duress. Many cultural items were purchased or taken from communities under the misguided assumption that Indigenous peoples would soon disappear; therefore, their cultures needed to be documented and preserved.

Although we cannot change the past, acknowledging this harm is a crucial step in fostering respectful, reciprocal, and sustainable relationships with the communities whose ancestors and cultural materials are housed in the Museum. Guided by principles of collaboration, transparency, and mutual learning, the Field Museum is committed to honoring the Indigenous knowledge, sovereignty, cultures, and histories that inform its work.

Repatriation and tribal relations

n 1990, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) was passed, providing a framework for the Field Museum to return human remains to their descendants. The Act also enables the Museum to return important cultural items to the communities who created and used them. Using the NAGPRA guidelines, the Museum identifies human remains and cultural items that are eligible for repatriation.

The Center for Repatriation, Tribal Relations, and Provenance Research facilitates repatriation requests through consultation with Indigenous communities and lineal descendants, which includes respecting sovereignty and traditional knowledge, responding to information requests, and providing access to the Museum’s extensive collections. Additionally, the Center assists with grant proposals and supports co-curation projects with Indigenous communities.

Turning scientific knowledge into action

In 1994, during the Field Museum’s centennial year, a small group of researchers began to organize a new Center to take Field Museum research and translate it into action to protect and restore the places that are critical to life on Earth—and to improve the quality of life for all. This was the founding of the Keller Science Action Center.

Spearheaded by Debra Moskovits, the team made its first expeditions to South America to perform the Museum’s first rapid biological inventories: documenting natural areas and the species that live there in order to make recommendations for conservation. These efforts have led to the protection of more than 33 million acres of forests and waters.

Since its establishment, the center has focused on the Chicago region and the high-biodiversity Andean foothills and Amazon forests of Ecuador, Peru, Colombia, and Bolivia. In Chicago, researchers engage communities and youth in environmental restoration and stewardship. In the Amazon, rapid inventory teams share their findings with local leaders and issue formal scientific reports that can inform public policy and conservation efforts.

Conservation ecologist Corine Vriesendorp in Colombia on Rapid Inventory 29, a trip to document rare and unknown species of plants and animals.

SUE makes a splash

In 2000, SUE, the largest T. rex specimen ever discovered, was unveiled to an adoring public that shares our passion for paleontology. This T. rex, the largest and most complete skeleton of its kind, is named for Sue Hendrickson, who discovered it in 1990 in South Dakota. After the museum purchased SUE, staffers spent more than 30,000 hours preparing the skeleton (plus another 20,000 hours building the exhibit).

John Weinstain: @Field Museum of Natural History

On May 17, 2000, SUE was unveiled in Stanley Field Hall.

Continuing Excellence in Collections

Field Museum conservators and curators have made important contributions to conservation science, and continue to contribute to best practices and industry standards for collection care.

Among the methods refined at the Field Museum anthropology collections are multiband photogrammetry, pheromone trapping for moth control, positive-pressure humidity control in display cases, low-energy methods for controlling humidity for corrosion prevention in metals, and automating the collection and processing of microfade testing data.

Other innovations include a process of dying Japanese papers to color-match existing pigments in organic materials, removing prior installations of display mounts from items, testing items and displays for heavy metals, pesticides, plastics, and testing materials for safety in the construction of display cases and storage housings..

Persistence through the COVID-19 pandemic

The Field Museum closed its doors for the first time since relocating in 1921 during the COVID-19 pandemic. After shelter-in-place orders were issued by Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot and Illinois Governer J.B. Pritzker, the Museum was completely closed to the public and all staff except essential workers managing the facility and collections. The Museum was shuttered for four months, from March to July 2020.

Our scientists, staff, and community stuck together despite the many hardships caused by the pandemic. While the doors were closed, we ramped up our digital programs, bringing the wonder of scientific discovery to people in Chicago and around the world through the Field Museum Learning Connection and Virtual Field Summer Camps.

Regenstein Conservator JP Brown repurposed the Museum's 3D printers to create NIH-approved face shields. With the help of other Museum staff, he produced and delivered face shields locally and to the Navajo Nation, who had more COVID-19 cases than any of the surrounding states and were in desperate need of Personal Protective Equipment.

Field Museum scientists studying viruses, including zoonotic viruses like COVID-19, work to determine their origins and behavioral patterns. “Museums are incredible repositories of biodiversity information. We now have tools to study materials in museum collections in ways never before possible, putting us in an ideal position to get ahead of viruses and other disease-causing agents,” said John Bates, PhD, Curator of Birds in the Negaunee Integrative Research Center.

The museum re-opened to members on July 17, 2020, and to the public a week later at just 25% capacity for just four days a week with social distancing and COVID-19 safety measures in place.

Celebrating our second century

On December 31, 2021 the Field Museum concluded its Because Earth campaign, raising a record $316.2 million for the Museum’s future. Through the generous support of our extended family of donors, the Museum renovated Stanley Field Hall, opened several new areas and exhibitions, and formed four centers of excellence: the Gantz Family Collections Center, Keller Science Action Center, Negaunee Integrative Research Center, and Sue Ling Gin Center for Education and Public Programs.

Amplifying Native voices

The Field Museum is embarking upon a new chapter to amplify Native voices while respecting the requests of Indigenous communities. This shift arises from a need to reassess our historical practices, which often marginalized Indigenous perspectives.

A landmark initiative in this transformation is the exhibition Native Truths: Our Voices, Our Stories. Created in collaboration with over 100 Tribal representatives, Native Truths prioritizes Native voices and perspectives, showcasing authentic narratives about their histories and cultures.

Additionally, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) empowers Native Nations and lineal descendants to reclaim and assert control over their cultural heritage held by museums.In accordance with NAGPRA, the Field Museum requires consent from lineal descendants and Tribal representatives to display or allow access to human remains and certain cultural items. The Field Museum has also covered display cases containing these cultural items, which the Museum acquired and displayed without consent.

Moving forward, the Field Museum aims to balance its educational mission with a genuine respect for Indigenous communities. For the time being, the covered display cases serve as a reminder that genuine engagement involves listening and evolving, ultimately fostering a future built on collaboration and respect for Native voices.

Leading-edge research

Field Museum scientists continue making discoveries through groundbreaking research on the items in our collections and in labs and out on field sites far beyond our walls.

Our botanists and mycologists are internationally recognized leaders in plant and fungi evolution and ecology, producing research that informs conservation and climate policy recommendations.

Field Museum paleontologists investigate early mammal relatives, marine reptiles, ancient turtles, fossil fishes, cryptic invertebrates, and of course, dinosaurs.

Meteoritics researchers and cosmochemists study presolar grains—real stardust— and extraterrestrial matter preserved in Earth's sediments and craters to decode data about our parent stars and the evolution of our galaxy.

Our anthropologists explore how humans impact their environments; how economic systems work, vary, and change; how life in cities emerged and how urban life influences our existence today; and explain the rise and fall of civilizations—including our own.

Zoologists at the Field are continually innovating in collections databasing; imaging; implementing Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to analyze spatial data on animal life, and bioinformatics: uncovering and sharing new-found knowledge of the diversity of life, and the processes that shape it.

Resilience leads to record-breaking growth

In 2022, we welcomed 1,018,002 visitors—a record year for annual attendance. The Field Museum ranks in the top 25 most-visited museums in the United States.

The next chapter

Much like life on Earth itself, the Field Museum is always evolving. Every day, our scientists and researchers are out exploring: from deserts to jungles to cities. Our conservators and exhibition designers are preserving and preparing brilliant examples of Earth’s power, beauty and diversity for visitors to discover. All while our Museum staff welcome guests from every corner of the globe.

We’re always working to discover new things: species to study, mysteries to solve, problems to tackle, challenges to confront. Past, present, and future, our work has been and always will be driven by a love for our planet—and the 8 billion people who call it home.